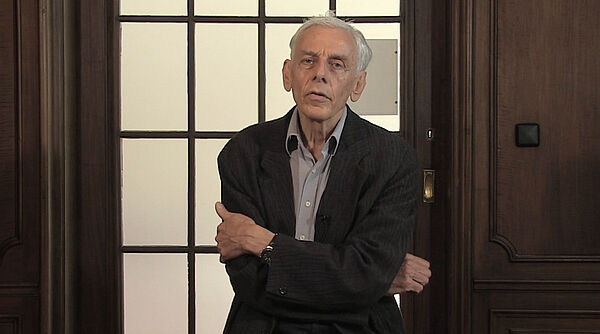

Luca Giuliani, Dr. phil.

Rector of the Wissenschaftskolleg (2007–2018), Professor (emer.) of Classical Archaeology

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

Born in 1950 in Florence, Italy

Studied Classical Archaeology, Ethnology, and Italian Literature at the University of Basel and at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (LMU Munich)

Project

A Face for Socrates: The Making of Ancient Greek Portraits

This is the title of a book that I am writing in collaboration with Maria Luisa Catoni (Fellow 2009/2010), to be published by Oxford University Press in 2026. It deals with the portrait that was dedicated to Socrates’ memory by friends or pupils, sometime after he had been tried and executed, but before his official rehabilitation—at a time when he was still considered a public criminal. We have already published papers on this subject. Writing a monograph now forces us to widen the scope and to examine the tradition of ancient Greek portraiture in general. This means also to revisit the most relevant scholarship on the sub¬ject, which is strongly rooted in a very specific German culture, highly sophisti¬cated and at the same time deeply dated. Complex problems sometimes become easier to manage when you look at them from far away. In our case, the necessi¬ty to address a wider English audience, while at the same time keeping our text brief and clear, has helped us to gain a new perspective. We are now beginning to see the outlines of a theory of ancient portraiture as being both similar to and profoundly different from its modern counterpart, with the portrait of Socrates at its centre.Recommended Reading

Catoni, Maria Luisa, and Luca Giuliani. “Socrates Represented: Why Does He Look Like a Satyr?” Critical Inquiry 45 (Spring 2019): 681–713. https://doi.org/10.1086/702595.

—. “Der verurteilte Philosoph, die Satyrn und das Hässliche: Das frühe Sokrates-Porträt im Kontext.” Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 136 (2021): 151–197.

Colloquium, 17.03.2020

Did the Ancient Romans Copy Greek Masterpieces? A Transatlantic Controversy

This question has been the subject of a controversy over the past 30 years, with the "Revisionists" opposing the "Orthodox" (my terminology; the latter mainly German speaking, the former mainly based in the US). It has been (and is) a strange controversy, because the two parties consistently refrain from speaking to each other. I shall proceed in six steps:

1. The first large findings of ancient sculptures occurred in Rome in the 15th and 16th centuries; rich people were eager to collect them, but nobody was able to bring the material into some kind of historical order. The first successful attempts to do so are due to antiquarian scholars of the 18th century, who began to combine archaeological findings with information derived from ancient literary sources.

2. From this emerges, in the 19th century, the German "Orthodoxy". One of its greatest representatives is Adolf Furtwängler (1853-1907) with his fundamental book: "Masterpieces of Greek Sculpture" (1893; English translation 1895). Furtwängler's aim was to use Roman copies to reconstruct the lost masterpieces of Classical Greek sculpture: bronze statues of the 5th and 4th centuries BC that are mostly lost to us, because they were melted down in Late Antiquity. I shall try to show how Furtwängler proceeds and what methods he relies on.

3. For the "Revisionists" I shall focus on Miranda Marvin (1941-2012) and her monograph The Language of the Muses. The Dialogue between Roman and Greek Sculpture (2008). Marvin holds Furtwängler's approach to have been deeply biased, because he used Roman statues as a transparent medium in order to recover something that he considered (or hoped) to be Greek; Marvin proposes to look at same statues as specific products of Roman culture. But the Revisionist’s argument goes further: They use the term "Roman copies" only in quotation marks, considering the concept to be a modern (German) myth; they explicitly claim that exact copies did not exist in Antiquity. But what exactly do we mean by "exact" - and what exactly is a copy in the first place?

4. I would like to check (and to reject) the Revisionist’s claim, relying mainly on a complex of plaster casts, found in Baiae on the Gulf of Naples in 1954. You shall have to look at fragments that are of little esthetic appeal, but of considerable historical interest.

5. The approaches of the Orthodox and the Revisionists are clearly opposite to each other - but there is one surprising point of agreement: they both consider copying to be a mechanical enterprise, unworthy of a true artist. This is why Furtwängler was not interested in Roman art (because he took the Romans to be mere copyists), and this is why the Revisionists, who want to defend the originality of Roman art, argue against the existence of Roman copies. Where does this negative image of copies come from? I shall focus on two decisive turning points: first, the creation of art academies since the 16th century, whereby artists emancipated themselves from the guilds and intellectualized their training, concentrating more on invention than on execution, more on the mind then on the craft; and second, what in German is called "Genieästhetik": the belief, emerging in the late 18th century, that a true artist does not follow rules but creates something new out of the depth of his own subjectivity. Under these terms copying indeed becomes the opposite of art.

6. But does this opposition lead us to a better understanding of ancient copies? I think it does not. Roman sculptors did not merely copy Greek masterpieces - they actually invented copying. This implied the investment of care and effort in order to achieve a high degree of fidelity to the originals; at the same time such copies are everything but self-effacing - on the contrary: they confidently display the virtuosity of their craftsmanship. It is exactly this combination of fidelity and conspicuous artistry that makes out the (to some extent: paradoxical) sophistication of Roman copying.

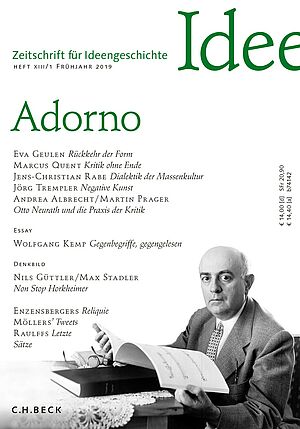

Köpfe und Ideen 2018

“By end of the year the group is more youthful . . .”

Luca Giuliani in an interview with Lothar Müller

Publications from the Fellow Library

Giuliani, Luca (2016)

Michelangelos Quader : ein Nachtrag

Giuliani, Luca (Basel, 2015)

Das Wunder vor der Schlacht : ein griechisches Historienbild der frühen Klassik Jacob-Burckhardt-Gespräche auf Castelen ; 30

Giuliani, Luca (2015)

How id the Greeks translate traditional tales into images?

Giuliani, Luca (2013)

Giuliani, Luca (2013)

Sarcofagi di Achille tra oriente e occidente : genesi di un'iconografia

Giuliani, Luca (S.l., 2013)

Routi haishi shitou - Mikailangqiluo de Loulunzuo Meidiqi mudiao Fleisch oder Stein - Michelangelos Grabstatue des Lorenzo de Medici <chin.>

Giuliani, Luca (2013)

Giuliani, Luca (München, 2013)

Konservative Ästhetik Zeitschrift für Ideengeschichte ; 7.2013,3

Giuliani, Luca (Göttingen, 2013)

Possenspiel mit tragischem Helden : Mechanismen der Komik in antiken Theaterbildern Historische Geisteswissenschaften ; 5

Giuliani, Luca (Chicago, 2013)

Image and myth : a history of pictorial narration in Greek art Bild und Mythos. <engl.>

Events

Luca Giuliani

Luca Giuliani | Benjamin Oldroyd | Bénédicte Zimmermann

Luca Giuliani

Luca Giuliani | Veronika Tocha

Luca Giuliani

Luca Giuliani

Luca Giuliani | Susanne Muth

Luca Giuliani

Luca Giuliani

Luca Giuliani

Luca Giuliani | Franco Moretti

Luca Giuliani | Franco Moretti

Luca Giuliani